Community

A Civil War Camp was Located Right Here in Central!

By Vicki Carney

By Vicki Carney

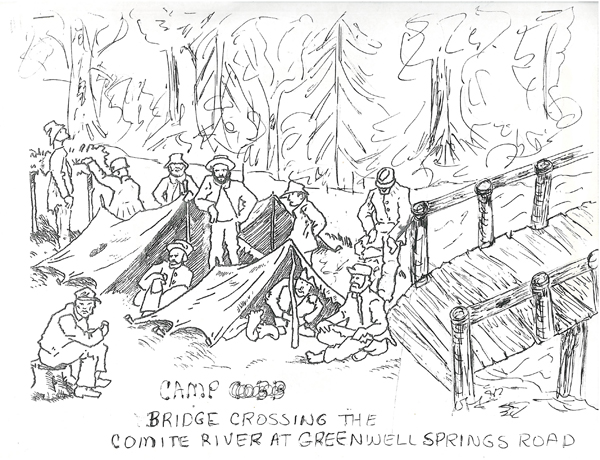

If you asked me how many times I have passed Old Greenwell Springs Road at Frenchtown Road, I would say thousands of times in the past 35 years. It wasn’t until recently that I started reading The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies that I realized the historical importance of where Old Greenwell Springs Road crossed the Comite River – just two blocks west of St. Alphonsus Catholic Church. This confederate camp was called Camp Breckinridge or Camp on Comite River. At one time Old Greenwell Springs Road was Greenwell Springs Road. It was not until the existing bridge was built that the road was straightened and part of the road was cut off. That part of the road that was cut off is called Old Greenwell Springs Road. (Not to be confused with Old Greenwell Springs Road that is close to Liberty Road).

General Breckinridge had been the Vice-President of the United States. When the Civil War broke out he was appointed Major General in the Confederate States Army. After Vicksburg, he arrived at Camp Moore in 1862. He was then ordered to march to Baton Rouge. He and his troops reached the Comite River at Greenwell Springs Road (now called Old Greenwell Springs Road) on Monday, August 4, 1862. The General wrote that the sickness had been appalling. He started out with 3,000 men but by the time he and his troops marched to Camp on the Comite he only had 2,600 able-bodied men. These poor soldiers had only from the afternoon of the 4th until 11 p.m. of that same day to rest and prepare for battle before marching into the Battle of Baton Rouge some ten miles from Camp Breckinridge or Camp on the Comite River. That was only a couple of hours! Following the horrific battle in Baton Rouge, Breckinridge returned his command to the Comite River. He wrote the following in his report of September 30, 1862 about the Battle of Baton Rouge: “The enemy were well clothed, and their encampments showed the presence of every comfort and even luxury. Our men had little transportation, indifferent food, and no shelter. Half of them had no coats, and hundreds were without either shoes or socks.” A few days after the battle, Breckinridge left Greenwell Springs and occupied Port Hudson with a portion of the troops under the command of Brigadier General Ruggles. Brigadier General Bowen, who had just arrived in Greenwell Springs, was ordered to the Camp on the Comite River to “observe Baton Rouge from that quarter, to protect our hospitals, and to cover the line of communication between Clinton and Camp Moore (a major Confederate training camp.)

Many troop leaders wrote field reports from Camp Breckinridge or Camp on the Comite River. 1) Captain John A. Buckner, Assistant Adjutant-General, C.S. Army, commanding First Brigade First Division, wrote from the Comite River, ten miles from Baton Rouge, LA, August 9, 1862. 2) Col. Jeptha Edwards, Thirty-first Alabama Regiment, wrote from Camp Near Comite River, LA, August 8, 1862. 3) Captain John H. Millett, Fourth Kentucky Infantry, wrote from Camp Near Comite River, August 7, 1862. 4) Major J.C. Wickliffe, Fourth Kentucky Infantry, Headquarters Fifth Kentucky Regiment, wrote from Camp Near Comite River, LA, August 7, 1862. 5) Col. T.B. Smith, Twentieth Tennessee Infantry, commanding Fourth Brigade, wrote from Camp on Comite River, Louisiana, August 10, 1862. 6) Brig. Gen. Daniel Ruggles, C.S. Army, commanding Second Division, with Return of Casualties, Camp Breckinridge, August 9, 1862. He reported that “on the night of August 4 this division proceeded from Comite River Bridge, marching left in front; … (some of his troops) reached Ward’s Creek Bridge, on the Greenwell Springs and Baton Roads, about 3 a.m.” He also said there was a “prevalence of thick fog.” In this report is an explanation of how Lieutenant Todd was killed and how “Colonel Allen also fell dangerously wounded.” 7) Col. J.W. Robertson, Thirty-fifth Alabama Infantry, commanding First Brigade, wrote from Camp on Comite River, LA, August 7, 1862. 8) Lieu. Col. Edwin Goodwin, Thirty-fifth Alabama Infantry, wrote from Camp on Comite River, LA, August 7, 1862. 9) Lieu. Col. M.H. Cofer, Sixth Kentucky Infantry, wrote from Comite River, LA, August 7, 1862. 10) Col. Gustavus A. Breaux, Thirtieth Louisiana Infantry, Headquarters Second Brigade, wrote from Camp Near Comite River, LA, August 8, 1862. He reported: “The troops, exhausted by fatigue and crying for water, were thrown in utter confusion.” 11) Lieu. S.E. Hunter, Fourth Louisiana Infantry, wrote from Camp Near Comite, August 7, 1862. 12) Capt. Thomas Bynum, Boyd’s Battalion, Stewart’s Legion writing from Comite Bridge, LA, August 8, 1862.

These reports, both Union and Confederate, are fascinating to read. The reports give the reader a basic understanding of how the Battle of Baton Rouge transpired. You can find the volumes at Bluebonnet Library, Port Hudson, Camp Moore, etc. The pages pertaining to this story can be found in the Civil War Notebook at the Central Library’s Local History Collection.

Note: This area was also one of the Camp Grounds at Greenwell Springs before the Civil War. When there was an outbreak of yellow fever, garrisons in the town moved to camps on the Comite and Amite River.

References:

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Washington Government Printing Office. 1886

Casey. Powell A., Encyclopedia of Forts, Posts, named Camps, and Other Military Installations in Louisiana, 1700-1981.

3 Comments